Rust: Proof of Concept, Not Replacement

CVE is cheap compared to this.

You were told Rust would kill C.

You were told memory safety is the future.

You were told the borrow checker would save billions.

Here's the part nobody wants to say out loud in 2025:

In roughly 8-12 years the biggest cost in software will no longer be memory-safety CVE payouts.

It will be the multi-hundred-billion-dollar bill from trying to

keep 2025-era Rust codebases alive when the next wave of breaking

changes hits tokio, axum, hyper, tower - and eventually serde - all

cascading through your dependency tree at once.

I. The Specification Problem

The Elephant in the Room: Rust Has No Standard

Before we talk about dependency hell, let's talk about why it's inevitable.

The language is defined by whatever rustc (the compiler) does today. Not by a standard. Not by a spec. By a compiler that changes every 6 weeks.

Yes, "The Rust Reference" exists. It explicitly states: "this book is not normative" and "should not be taken as a specification for the Rust language." It also warns: "This book is incomplete." That's not a specification - that's documentation.

| Attribute | C | C++ | Ada | FORTRAN | COBOL | Go | JavaScript | Rust (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official standard | ISO/IEC 9899:2024 | ISO/IEC 14882:2024 | ISO/IEC 8652:2023 | ISO/IEC 1539:2023 | ISO/IEC 1989:2023 | Go Spec (formal)* | ECMA-262 | None |

| First standardized | 1989 | 1998 | 1983 | 1966 | 1968 | 2012 | 1997 | Never |

| Language defined by | Formal standard | Formal standard | Formal standard | Formal standard | Formal standard | Formal spec | Formal standard | rustc behaviour |

| Independent compilers | 6+ mature | 5+ mature | 3+ mature | 5+ mature | 4+ mature | 2 (gc, gccgo) | 10+ engines | ~0 |

| Safety-critical cert possible | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited | N/A | Pay Ferrocene |

| 2035 compile: 2015 code | ~100% | ~99% | ~100% | ~100% | ~100% | ~95% | ~99% | <30%? |

* Go has a formal, normative specification maintained by the Go team, but it is not an ISO/IEC standard like C, C++, or Ada.

Yes, even JavaScript - the language systems programmers love to mock - has had a formal ECMA standard since 1997. Rust, the "serious systems language," has been around for 10+ years and still doesn't have one.

Why This Causes Dependency Hell

The causal chain nobody talks about:

No standard

→ No stable foundation to build against

→ Everything depends on specific rustc version

→ Crates depend on specific rustc behavior

→ When rustc changes, crates must change

→ Synchronized ecosystem breakage

→ DEPENDENCY HELLIn C, the causal chain is different:

ISO standard exists

→ You write against the standard

→ Compiler is a replaceable tool

→ Dependencies target the standard, not the compiler

→ 20 years later: still compiles

→ STABILITYThis isn't a tooling problem. It's not a "skill issue." It's an architectural decision that Rust made, and now the entire ecosystem inherits its consequences.

The Ferrocene Absurdity

Here's a delicious irony that should make every Rust evangelist uncomfortable:

Why? Because safety-critical industries require a formal, verifiable specification. And Rust doesn't have one.

This isn't speculation. From Ferrous Systems' own documentation:

Think about what this means:

Rust is marketed as the "safe" language for systems programming. Yet when actual safety-critical industries (medical devices, cars, trains, aircraft) want to use it, they cannot - unless a third party first writes the specification that the Rust Foundation refuses to produce.

This is like a car manufacturer marketing their vehicle as "the safest on the road" - but when regulators ask for crash test data, the manufacturer says "just trust us, we tested it internally." So a third-party company has to independently certify the car, at their own expense, and charge customers for access to that certification.

The FLS was donated to the Rust Project in March 2025:

But note: FLS was born from third-party necessity, not core team foresight. Ferrocene achieved qualification in October 2023 (TÜV SÜD certificate). The Rust team's own Reference? It explicitly states it is "not normative" and "should not be taken as a specification" - not something you can certify against.

No adults in the room.

A language ecosystem where technical criticism is met with "skill issue" and mass dismissal, but a formal specification remains "not a priority" after 10 years, has made its governance choices clear.

Sources

- Ferrous Systems Blog - The Ferrocene Language Specification is here! (2023)

- Rust Project Blog - Adopting the FLS (March 2025)

- GitHub - rust-lang/fls (formerly ferrocene/specification)

- Rust Reference - Introduction ("This book is incomplete... this book is not normative")

- Lobsters - Ferrocene: ISO 26262 and IEC 61508 qualified

When your pacemaker needs to run "memory safe" code, your safety auditor asks for a specification. Rust's official answer? "Trust the compiler."

(To be fair: even C is often restricted or banned in Class III medical devices under IEC 62304. But at least C has a standard to be evaluated against. Rust doesn't even have that.)

II. The Cognitive Tax

The Cognitive Load Nobody Talks About

There's another cost that doesn't show up in CVE databases or dependency graphs: cognitive load.

The Rust community frames the borrow checker as "the compiler does the hard work for you." This is a half-truth that obscures a fundamental tradeoff.

C/C++ (Experienced Developer)

Resource management is internalized. It's like driving a manual transmission - you don't consciously think about shifting gears, you just do it. Yes, mistakes happen. But this leaves cognitive room for domain logic, architecture, edge cases, and "what if this input is malformed?"

Rust (Any Developer)

Resource management is externalized to the compiler. You must translate your mental model into the borrow checker's language. That translation is cognitive load. And it doesn't fully disappear - every new function, every new struct, every lifetime annotation demands it again.

Here's the key distinction that Rust evangelists consistently miss:

Rust asks: "Can you PROVE to me it's safe, in MY specific syntax?"

Those are two fundamentally different cognitive tasks.

An experienced C programmer thinks: "This pointer comes from the caller, I shouldn't free it." Done. One mental note, move on.

A Rust programmer must express that same knowledge as lifetime annotations, reference types, ownership transfers - and if the borrow checker disagrees with your (correct) mental model, you refactor until it's satisfied. The knowledge was already there. The proof is the tax.

The Syntax Disaster: A Design Flaw, Not a Feature

The borrow checker's core ideas fit in three sentences:

- Every value has one owner

- You can borrow mutably or immutably

- Borrows can't outlive the owner

A junior developer can understand this in an afternoon. The concept is approachable.

But as we saw in the previous section, applying those concepts - proving safety to the compiler in its specific language - is already cognitively taxing. You're not just thinking about safety; you're translating your mental model into the borrow checker's proof system.

Now here's where Rust delivers the killing blow: the syntax.

A difficult cognitive task, expressed through a nightmarish syntax, becomes virtually impossible to retain.

Rust

fn process<'a, T: Clone + Send + 'static>(

data: &'a mut Vec<Arc<Mutex<Box<dyn Handler + Send>>>>,

) -> Result<impl Iterator<Item = &'a T>, Box<dyn Error>>Ada

function Process (Data : in out Handler_Vector)

return Handler_ResultRust (from our threadpool)

sender: Option<mpsc::Sender<Box<dyn FnOnce() + Send + 'static>>>C

void (*task)(void *arg);Three years after learning Rust, developers still can't reproduce these signatures from memory. Meanwhile, C syntax learned 20 years ago remains instantly accessible.

Why? Because the human brain stores patterns, not symbol salad.

The Compound Effect

This is the trap that Rust evangelists don't acknowledge:

Either factor alone might be manageable. Combined, they create a language that actively fights human memory and cognition.

The Symbol Inventory

| Language | Core Symbols to Memorize |

|---|---|

| C | * & [] () -> . |

| Ada | Words: in, out, access, record, is, begin, end |

| Rust | & &mut 'a 'static :: <> [] () -> . ? ! dyn impl Box Arc Rc RefCell Mutex + lifetime combinatorics |

Rust requires roughly double the symbol vocabulary of C - and then layers lifetime combinatorics on top.

This Was a Choice

Rust's designers came from ML/Haskell academia, where 'a and <T: Trait + 'static> are considered "normal." They optimized for expressiveness. They forgot to ask: is it readable?

Ada solved readability in 1983 with a simple principle: code is read more often than it's written - optimize for reading.

Rust ignored 40 years of lessons about language ergonomics.

Rust could have been:

// Hypothetical "readable Rust"

fn process(data: borrowed mutable Vec<Handler>) -> Result<Handler>Instead we got:

fn process<'a>(data: &'a mut Vec<Handler>) -> Result<Handler, Error>And that's the simple version. Real-world Rust quickly escalates to:

fn process<'a, 'b, T: Handler + Send + 'static>(

data: &'a mut Vec<Arc<Mutex<Box<dyn T + 'b>>>>

) -> Result<impl Iterator<Item = &'a T>, Box<dyn Error + 'static>>This is not complexity demanded by the problem domain. This is accidental complexity introduced by poor syntax design.

The "Write-Only Language" Effect

There's an old joke about Perl being a "write-only language" - easy to write, impossible to read later.

Rust has achieved something worse: hard to write AND hard to read.

C code from 1985 remains readable today. Ada code from 1990 remains readable today. Rust code from last month requires a mental compiler to decode.

When experienced developers say "I tried Rust three times and it just doesn't stick" - this is why. It's not the concepts alone. It's not intelligence. It's the combination of cognitive proof-work AND syntax that actively fights human memory.

And no amount of "just practice more" fixes a fundamental design flaw.

The Cloudflare Paradox

In 2025, Cloudflare suffered a significant outage. The code was written in Rust. The borrow checker was satisfied. Memory safety was guaranteed.

The bug? A malformed input file that the code didn't handle correctly.

This illustrates what we might call the Cloudflare Paradox:

The borrow checker guarantees your pointers are valid. It says nothing about whether your logic is correct, your inputs are validated, or your edge cases are handled.

But here's the insidious part: when a language markets itself as "safe," developers develop a false sense of security. "It compiles, therefore it's correct" becomes an unconscious heuristic. The cognitive attention that would have gone to "what if this file is malformed?" gets consumed by wrestling with lifetimes instead.

The Rust community's response to such incidents is predictable: "That's not a memory safety bug, that's a logic bug. Rust never claimed to prevent logic bugs."

Technically true. But also missing the point entirely.

The question isn't whether Rust claims to prevent logic bugs. The question is: where does the cognitive attention freed by "memory safety" actually go?

- Does it go to domain logic and edge case analysis?

- Or does it get consumed by the borrow checker's demands?

- Or worse - does a false sense of security emerge, reducing vigilance overall?

We don't have studies on this. But we do have incident reports. And they suggest the answer isn't as flattering as the marketing implies.

The Threading Tax: A Concrete Example

Let's look at something every backend developer needs: a thread pool with callbacks. This is not an exotic data structure - it's bread-and-butter concurrent programming.

C Version: 60 lines, zero cognitive overhead

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct {

void (*callback)(void* data); // Function pointer

void* data; // Data pointer

} Task;

typedef struct {

Task* tasks;

int capacity, count, head;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

pthread_cond_t not_empty;

int shutdown;

} TaskQueue;

TaskQueue queue = {0};

void queue_push(void (*cb)(void*), void* data) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&queue.lock);

int idx = (queue.head + queue.count) % queue.capacity;

queue.tasks[idx].callback = cb;

queue.tasks[idx].data = data;

queue.count++;

pthread_cond_signal(&queue.not_empty);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue.lock);

}

void* worker(void* arg) {

while (1) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&queue.lock);

while (queue.count == 0 && !queue.shutdown)

pthread_cond_wait(&queue.not_empty, &queue.lock);

Task t = queue.tasks[queue.head];

queue.head = (queue.head + 1) % queue.capacity;

queue.count--;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue.lock);

if (t.callback == NULL) break;

t.callback(t.data);

}

return NULL;

}The mental model: pointers go in, pointers come out, mutex protects shared state. That's it.

Rust Version: Same functionality, triple the ceremony

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex, Condvar};

use std::collections::VecDeque;

// First, you need to understand this type signature:

type Job = Box<dyn FnOnce() + Send + 'static>;

// ^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^ ^^^^ ^^^^^^^

// | | | "no short lifetimes"

// | | "safe to send across threads"

// | "callable once, dynamic dispatch"

// "heap-allocated, owned"

struct ThreadPool {

workers: Vec<thread::JoinHandle<()>>,

queue: Arc<TaskQueue>, // Arc: shared ownership

}

impl ThreadPool {

fn execute<F>(&self, f: F)

where

F: FnOnce() + Send + 'static, // Every callback needs these bounds

{

let mut jobs = self.queue.jobs.lock().unwrap();

jobs.push_back(Some(Box::new(f)));

self.queue.condvar.notify_one();

}

}

// Want shared state? More wrappers:

let results = Arc::new(Mutex::new(Vec::new()));

for i in 0..20 {

let results = Arc::clone(&results); // Clone Arc each iteration

pool.execute(move || { // move: closure takes ownership

let mut r = results.lock().unwrap();

r.push(i);

});

}Arc - atomic reference counting for shared ownershipMutex - mutual exclusion for interior mutabilityCondvar - condition variable for signalingBox<dyn T> - heap allocation with dynamic dispatchFnOnce - closure trait for one-time callableSend - marker trait for thread-safe transfer'static - lifetime bound meaning "no borrowed references"move - keyword to transfer ownership into closureArc::clone() - explicit cloning before each closure.lock().unwrap() - fallible lock acquisitionIn C, you need: mutex, condvar, function pointer, void pointer.

Four concepts. Not eleven.

The Error That Teaches Nothing

Watch what happens if you forget Arc::clone() in Rust:

for i in 0..20 {

// OOPS: forgot Arc::clone()

pool.execute(move || {

results.lock().unwrap().push(i);

});

}

// ERROR: value moved in previous iterationThe compiler catches this. Good. But the fix isn't

"add a mutex" - you already have a mutex. The fix requires understanding

Rust's ownership model deeply enough to know that Arc::clone() creates a new owned handle that can be moved into the closure independently.

In C, you'd just pass the pointer. The pointer doesn't care how many functions reference it.

The Rust programmer's bug: "I forgot to clone the Arc before moving it into the closure because the borrow checker's ownership model requires each closure to have independent ownership of the reference-counted handle."

One of these fits in working memory. The other requires a whiteboard.

But Rust Catches Data Races!

Yes. Rust's type system prevents data races at compile time. This is genuinely valuable.

But notice what it doesn't prevent:

- Deadlocks (two threads waiting on each other's mutexes)

- Livelocks (threads spinning without progress)

- Priority inversion

- Logic errors in concurrent algorithms

- Performance bugs from lock contention

These are the bugs that actually kill production systems. Data races are relatively rare in well-structured C code with proper mutex discipline. The hard concurrency bugs are logical, not mechanical - and Rust's type system provides zero help there.

Meanwhile, the cognitive overhead of Arc<Mutex<RefCell<Box<dyn Trait + Send + Sync + 'static>>>> is very real, very constant, and very much consuming attention that could go elsewhere.

III. The Defenses (And Why They Fail)

The "Skill Issue" Defense

When you raise these concerns in Rust communities, the response is often: "Sounds like a skill issue. Once you internalize the borrow checker, it becomes natural."

This is partially true - and completely irrelevant to the argument.

Yes, experienced Rust developers get faster at satisfying the borrow checker. But "faster" isn't "free." The cognitive overhead decreases but never reaches zero, because:

- Every new codebase has new ownership patterns to decode

- Every new function signature requires lifetime reasoning

- Every refactor risks borrow checker regressions

- The ecosystem's

Rc<RefCell<Box<dyn Trait>>>patterns add layers of indirection

Compare this to C, where an experienced developer's resource management is genuinely automatic - not "faster translation to compiler syntax," but no translation needed at all.

The "skill issue" defense also carries an uncomfortable implication: if Rust requires mass "re-skilling" of the entire industry, that's not a feature - that's a cost. A multi-billion-dollar cost in training, reduced productivity during learning curves, and permanent cognitive overhead for patterns that were previously internalized.

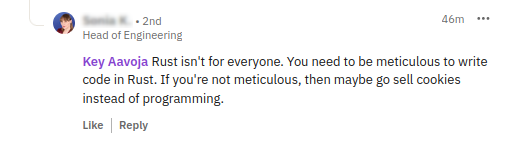

This isn't a hypothetical. Here's an actual response from a Head of Engineering to criticism of Rust's cognitive overhead:

The comment was later edited to sound more professional - but it's still a strawman. The polished version claims I'm "advocating for developers to ignore code quality." I never said that. The original sentiment just said the quiet part out loud.

The "Alternative Compilers" Myth

"But gccrs and rust-gcc are coming! We'll have compiler diversity!"

These projects are attempting to implement a language that has no specification. They're reverse-engineering rustc's behavior. Every edge case, every undefined behavior, every quirk - they have to match what rustc does, because rustc IS the definition.

This isn't like having GCC and Clang both implement ISO C.

This is like trying to build a second JVM by watching the first one and guessing.

C Compiler Ecosystem

GCC implements ISO C

Clang implements ISO C

MSVC implements ISO C

→ They agree because they follow the same spec

Rust Compiler "Ecosystem"

rustc implements... rustc

gccrs tries to copy rustc

mrustc tries to copy rustc

→ They can only agree by mimicking one implementation

How's that alternative compiler coming along? gccrs has been in development for 10+ years and still cannot compile the Rust core library - let alone complex async code. Without a spec to implement against, they're reverse-engineering a moving target.

The Bootstrapping Problem

Here's a question Rust evangelists don't like to answer:

Where's the fully self-hosted toolchain?

Why can't Rust bootstrap itself without C++?

The Rust compiler (rustc) is written in Rust. Sounds impressive, right? Except:

- rustc depends on LLVM - which is written in C++

- LLVM is ~5 million lines of C++ - that's not going away

- The Rust standard library links to libc on most platforms

- Cargo depends on libgit2 (C), libssh2 (C), and OpenSSL (C)

This means: to build Rust, you first need a working C/C++ toolchain. Rust is not self-sufficient. It's a layer on top of C/C++ infrastructure.

C Toolchain

GCC can compile itself.

Linux kernel is written in C.

libc is written in C.

→ Complete stack, top to bottom

Rust Toolchain

rustc needs LLVM (C++).

No production Rust kernel exists.

std links to libc (C).

→ Parasitic on C/C++ ecosystem

There are experimental projects like mrustc (a C++ Rust compiler for bootstrapping) and Redox OS (a Rust microkernel). But after 10+ years:

- mrustc can only compile old Rust versions (1.54)

- Redox is still experimental, not production-ready

- No Fortune 500 runs their infrastructure on a Rust kernel

As one commenter put it: "The long drop bog in the back yard isn't even built yet, let alone a fully plumbed in bathroom."

A language that claims to replace C/C++ but can't exist without C/C++ isn't a replacement. It's a tenant.

The LLVM Kernel Hell

The LLVM dependency becomes even more painful in kernel context. Here's what the Linux kernel documentation says:

Using GCC also works for some configurations, but it is very experimental at the moment. — Linux Kernel Rust Quick Start

Why is this a problem?

- Rust requires a specific LLVM version - the kernel may want a different one

- Cross-language LTO (Link-Time Optimization) requires exact LLVM version matching between Rust and C code

- Rust has out-of-tree patches for LLVM - applied to official Rust binaries but not vanilla LLVM builds

- bindgen needs libclang - yet another LLVM component to version-match

The result? Kernel.org has to maintain special toolchain bundles with pre-matched LLVM+Rust versions. Distros can't just apt install - they need specific version combinations that may not exist in their repos.

C Kernel Build (40 years)

gcc kernel.c

Works with GCC 4.x through 14.x

Any distro's packaged compiler

→ Just works™

Rust Kernel Build (2025)

Download special kernel.org toolchain

Set LLVM=1, LIBCLANG_PATH=...

Hope versions align

→ Configuration archaeology

From LWN.net: "LLVM is a fast-moving project with no API stability, so it's very difficult to use 'system LLVM'."

This isn't theoretical. It's the daily reality for anyone trying to build a Rust-enabled kernel on anything other than bleeding-edge distros.

IV. The Numbers

The Timeline Nobody Is Pricing In (Yet)

| Year | Event | Estimated global damage if unmitigated |

|---|---|---|

| 2023-2025 | axum 0.6→0.7→0.8, hyper 0.14→1.0, tower breaking changes | Already happened: mass ecosystem churn, 3-6 month migrations |

| 2027-2029? | Next major version wave (pattern: every 2-3 years) | If pattern holds: 3-12 month migrations per affected project |

| 2028-2032 | First wave of abandoned 2024-2028 crates | 30-50 % of crates.io effectively unmaintained |

| 2030-2035 | Edition churn + allocator & async-trait stabilizations | Every large Rust codebase becomes archaeology |

Heartbleed (2014) cost ~$500 million.

Log4Shell + every OpenSSL disaster combined < $5 billion.

A single synchronized dependency apocalypse across CDN edge, 5G core, payment processors, and blockchain nodes in ~2032?

Realistic downside: $50-500 billion.

The Cold Numbers (December 2025)

- crates.io: ~200 000 crates, growing 35-40 % YoY

- Average vendor folder (axum + tokio stack): 1.2-2.2 GB

- Percentage of crates that break semver on major bumps: 50-65 %

- Axum/tower/hyper/tokio stack: 4 breaking releases in the last 24 months

- serde: stable at 1.x since April 2017 - but what happens when 2.0 eventually ships and mass custom (de)serializers break?

The "Cargo.lock" Cope

"Just vendor your dependencies and lock everything!"

Sure. And now you have:

- A 2 GB vendor directory in your repo

- No security updates (enjoy your unpatched CVEs)

- Technical debt compounding every year

- A codebase frozen in 2025 amber

That's not a solution. That's palliative care.

The "Edition" Cope

"But Rust has Editions! Backward compatibility is guaranteed!"

The Edition system promises compatibility. But:

- Editions don't cover standard library behavior changes

- Editions don't cover compiler optimization changes

- Editions don't cover crate ecosystem compatibility

- Editions are promises from the rustc team - not guarantees from an independent standard body

When Python promised long-term Python 2 support, they eventually broke that promise. What makes the rustc team different? Good intentions?

A standard is a contract. A promise is just... a promise.

CVE Tax vs. Migration Tax

| Cost Type | C's CVE Tax | Rust's Migration Tax |

|---|---|---|

| Predictability | Known, bounded, insurable | Unknown, unbounded, uninsurable |

| Frequency | Occasional incidents | Continuous churn |

| Per-incident cost | Millions | Potentially billions (synchronized) |

| Mitigation | Static analyzers, sanitizers, careful coding, audits | Vendoring and prayer |

V. The Verdict

The Punchline

Fifteen years from now, the cheapest, most maintainable, and most predictable code running in production will still be the boring C daemon someone wrote in 2023 that still builds with:

make && ./serviceNo 2 GB vendor directory.

No Pin<Box<dyn Future<Output = Result<_, anyhow::Error>>>>.

No six-month migration because tokio finally stabilized async traits in edition 2033.

No compiler-as-specification roulette.

Final Score, Circa 2038

| Language | Has formal standard | Still compiles in 2038 | Dependency-hell tax | Memory-safety CVE tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Yes (ISO) | Yes | ~0 | Exists, but known & bounded |

| Rust 2025-era | No | Only if vendor-locked in 2027 | Hundreds of billions | Zero (until the rewrite bill arrives) |

The Bottom Line

Memory safety was never free.

We just haven't been sent the invoice yet.

And when a Rustacean tells you this analysis is a "skill issue," remember:

It's a governance decision. And Rust made theirs.

VI. The Signal

The NVIDIA Signal

Want to know what the world's most valuable company chooses for safety-critical firmware? Spoiler: it's not Rust.

In 2019, NVIDIA announced a partnership with AdaCore to rewrite security-critical firmware from C to Ada and SPARK - not Rust. The goal: ISO 26262 compliance for autonomous vehicles and embedded AI systems.

Fast forward to November 2025: NVIDIA engineers presented at DEF CON 33, explaining how SPARK is used to verify GPU-adjacent RISC-V firmware components. They've shipped over one billion cores since migrating their Falcon control processors to RISC-V in 2016.

"At scale, assurance must be engineered in, not inspected in: Use a language and toolchain that allows you to prove the absence of critical classes of defects."

Why SPARK over Rust?

| Capability | Rust | SPARK |

|---|---|---|

| Memory safety | ✅ Compile-time | ✅ Mathematically proven |

| Absence of runtime errors | Partial | ✅ 100% proven |

| Formal verification | ❌ | ✅ Mathematical proof |

| ISO 26262 / IEC 61508 certified tools | ❌ (Ferrocene is third-party) | ✅ TÜV SÜD certified |

| ISO standard | ❌ | ✅ ISO/IEC 8652:2023 |

| Track record in safety-critical | ~10 years | 40+ years |

NVIDIA's Daniel Rohrer, VP of Software Security, put it plainly: "Self-driving cars are extremely complex and require sophisticated software that needs the most rigorous standards out there."

They evaluated the options. They had the budget to choose anything. They chose SPARK.

The kicker? According to AdaCore: "Many of NVIDIA's early SPARK skeptics have now become SPARK evangelists."

What This Means for Rust

NVIDIA's choice has downstream effects:

- No NVIDIA engineering hours flowing into Rust's safety-critical ecosystem

- No NVIDIA validation for Rust in automotive/embedded AI

- No NVIDIA case studies that other OEMs can point to

- No NVIDIA money funding Rust tooling for ISO 26262 compliance

When the world's most valuable company needs firmware for autonomous vehicles - where bugs can kill - they don't choose Rust. That's not FUD. That's a signal.

The Rust community loves to cite "Big Tech adoption" - Google, Microsoft, AWS. But those are cloud/web companies. When you ask "Who uses Rust for safety-critical systems where people can die?" the room goes quiet.

NVIDIA answered that question. The answer was Ada/SPARK.

The Linux Kernel Reality Check

But wait - what about the Linux kernel? Surely that's the ultimate validation of Rust in systems programming?

Let's look at the actual numbers, not the headlines:

| Metric | Reality (December 2025) |

|---|---|

| C code in kernel | 11,000,000+ lines |

| Rust code in kernel | ~40,000 lines |

| Percentage Rust | ~0.36% |

| Production Rust drivers | Handful (Binder, experimental GPU drivers) |

| Core kernel in Rust | 0% (scheduler, VFS, memory management - all C) |

And here's what the headlines don't tell you:

Wedson Almeida Filho (August 2024): "I'm stepping down from the Rust for Linux project due to non-technical resistance from some maintainers."

Hector Martin (Asahi Linux lead, January 2025): Quit as upstream maintainer after conflict with C kernel maintainers over Rust DMA bindings.

Linus Torvalds himself described the situation at Open Source Summit Korea 2025 as having "almost religious war undertones."

Think about what this means:

- This was the ideal use case for Rust - new device drivers, optional, with Linus's explicit support

- Even with top-down blessing from Linux's creator, adoption is minimal

- Even with memory safety benefits, maintainers rejected the complexity

- Even after 3+ years of effort, key developers quit due to resistance

Greg Kroah-Hartman (Linux stable maintainer) said in late 2024 that Rust is at a "tipping point" - but that was optimism, not reality. The actual merged Rust code remains microscopic compared to the C codebase.

The kernel is C. The kernel will remain C. Your C skills are safe.

The Big Tech Illusion

When Rust advocates need examples, they reach for the same names: AWS, Cloudflare, Google, Microsoft, Discord.

Here's the uncomfortable truth about those examples:

What Big Tech Has

- Dedicated teams just for toolchain maintenance

- Locked rustc versions across entire org

- Budget to rewrite when things break

- Internal forks of critical dependencies

- Proprietary code nobody else can see or use

What You Have

- One team doing everything

- Whatever rustc your distro ships

- Budget for features, not rewrites

- Hope that crates.io stays compatible

- Actual shipping deadlines

This is the IBM Mainframe pattern:

→ Works perfectly... if you're a bank or government

→ Costs a fortune

→ Specialists are expensive and rare

→ Locked ecosystem

→ "Enterprise-grade" = "you can't afford it"

Rust at Big Tech:

→ Works perfectly... if you're AWS or Google

→ Requires dedicated toolchain team

→ Rust experts are expensive and rare

→ Locked to internal infrastructure

→ "Production-ready" = "if you have their resources"

When AWS says "we use Rust for Firecracker," that's not evidence that you should use Rust. That's evidence that a trillion-dollar company with unlimited engineering resources can make anything work.

Meanwhile, in the real world:

- A normal developer wants

apt install libfooand link - A normal developer wants plugins that work across versions

- A normal developer wants pre-built binaries they can actually use

- A normal developer doesn't have 6 months for a tokio migration

Rust's "success stories" are survivorship bias from organizations that can afford to paper over the problems. The failures don't write blog posts.

Big Tech also uses custom kernels, proprietary databases, and internal tools you'll never see.

The question isn't "can Google make it work?" - it's "can you?"

VII. Epilogue

The Waypoint, Not the Destination

After all the criticism above, let me be clear about one thing:

Compile-time memory safety without garbage collection is achievable. That's not nothing. That's a genuine contribution to computer science.

The borrow checker, for all its ergonomic costs, demonstrated that a type system can encode ownership and lifetimes in a way that eliminates entire classes of bugs at compile time. Before Rust, this was theoretical. After Rust, it's proven.

But here's the thing about proofs of concept: they're not the same as solutions.

Mechanized Semantics From the Beginning

The real problem isn't that Rust chose the borrow checker. It's that Rust was designed in 2010-2015, before we had the tools to explore the design space properly.

Today, we have:

- ML-assisted language design - models that can explore thousands of type system variations faster than any human team

- Mechanized semantics - formal specifications that are machine-checkable, not just prose documents

- 15 years of Rust ecosystem data - showing which patterns work, which cause pain, and where the cognitive costs concentrate

A language designed today could start with mechanized semantics from day one - not bolted on later by a third party for safety certification. It could explore alternatives to the borrow checker model: different approaches to linear types, region-based memory, capability systems, or something entirely new that optimizes for both safety and ergonomics.

Rust's a-mir-formality project is trying to formalize the MIR (Mid-level Intermediate Representation) after the fact. It's valuable work. But retrofitting formalization onto a mature language is fundamentally harder than designing with it from the start.

The Language That Replaces C Doesn't Exist Yet

This is the uncomfortable truth that neither C diehards nor Rust evangelists want to hear:

That's its lasting contribution.

But it's a waypoint, not the destination.

The language that truly replaces C/C++ in systems programming - with memory safety, ergonomic resource management, ecosystem stability, formal specification, and 50-year longevity - doesn't exist yet.

C will remain because it has a 50-year track record, formal standards, multiple independent compilers, and an ecosystem that doesn't break every 18 months.

Rust will remain because it proved something important and built real infrastructure on that proof.

But somewhere out there - maybe being designed right now, maybe waiting for someone to start - is a language that learns from both. One that has:

- Memory safety without the cognitive ceremony

- A formal specification from day one

- Stability guarantees backed by governance, not promises

- An ecosystem model that doesn't create synchronized dependency hell

- Ergonomics that don't require "re-skilling" an entire industry

When that language arrives, it won't replace C overnight. Nothing does. But it will make both C's manual memory management and Rust's borrow checker ceremony look like the historical artifacts they are.

Until then? Pick your tradeoffs carefully. And don't let anyone tell you there's only one right answer.